Majesty.

It was everywhere I looked in Newfoundland: the Long Range Mountains, the Tablelands, the sea cliffs, and the waves that crashed even in calm seas. The whole island, from Gros Morne National Park, to the Northern Peninsula, to Bonavista and then St. John’s radiated majesty.

Majesty. One lovely word that managed to crowd out the tangle of tasks, commitments, worries and inadequacies that usually fill my mind.

It was wonderful.

And to think, that our Newfoundland road trip stemmed from Parks Canada’s decision to make Parks and Heritage sites free for 2017. Of course we could have used the Parks Pass anywhere in Canada. It was probably the red chairs that did it. Canada Parks “Red Chair Experience Program” was started in Gros Morne National Park and it was vistas from those Gros Morne chairs that got me hooked. By spring 2017 I knew that the proper use of the Parks Pass would require a trip to Newfoundland. Now we have our own “red chair” photos.

We drove nearly the entire island of Newfoundland in one gas efficient rental car, staying in cabins where we could cook our own meals and changing locations every two days. It was our family’s first real road trip and I couldn’t have planned it on my own. I had help from the experts at Linkum Tours a Newfoundland based company that helped us create a custom self-guided tour that fit our family to a tee. I highly recommend this company to anyone looking to travel in Newfoundland & Labrador.

The landscape in Newfoundland is incredible and we experienced it immediately on the drive from the airport in Deer Lake to Rocky Harbour (a town made famous in 2014 when one of two blue whales washed up on its shores). The road wound through the scenery of northern Gros Morne National Park – craggy mountains that seemed to rise out of the waters of Bonnie Bay. One such mountain is the one for which the park is named: Mount Gros Morne at 806m. In French its name means “large mountain standing alone,” or more literally “great sombre.”

That afternoon we picnicked on mooseburgers at Lobster Cove Head lighthouse.

On our postprandial hike we scampered on fabulous layered limestone, chert and quartz stone. Their tilted and alternating layers clearly showed the geological periods in which they were created.

We also delighted in tide pools with seaweed (the most common were Fucales sp. like bladder wrack with air bladders to keep them upright at high tide), tiny shrimp-like crustaceans, periwinkles (sea snails), and even anemones. Finally the hike took us through dense, gnarled white spruce forest that looked enchanted in the light of the setting sun.

We ended the day with a stop at the Rocky Harbour playground, which should be nominated for playground with the best view. Then it was bedtime at Mountain Range Cottages.

The next day we drove from Rocky Harbour up the west coast of the northern peninsula on a highway known as the Viking Trail. The road took us past the stunning cliffs of the Long Range Mountains, part of the northern most Appalachian Mountains, and along the rugged shores of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

We stopped at Port Au Choix, a UNESCO World Heritage site, which has been occupied by human groups almost continuously for over four thousand years. First came the Maritime Archaic Indians, then Palaeoeskimo groups who lived in the area from 2800 to 1300 BP when the climate was cooler, and finally with a warming climate, ancestral Beothuk natives. Equaling the cultural history of the area was Port au Choix’s natural history, which we learned of hiking through the unique limestone barrens landscape.

The limestone and dolomite of the area originated as coral in a tropical sea 500 million years ago. The ancient seabed was pushed up when the African and American continental plates collided and has been weather by years of rain and frost. In some places, like the limestone barrens, this unrelenting weathering has shattered the rock to gravel. In other places, like the viewpoint along the trail, one can still find fossilized spirals (probably sea snails), evidence of the rock’s marine origin. From the top of the hill we also saw caribou, which use the limestone barrens in the summer and move inland to denser forest in winter.

After Port au Choix we continued to the northern tip of the Northern Peninsula where we stayed at the delightful Beachy Cove Cabins (loved the handmaid quilts on the beds). It was a mere 5-minute drive from another UNESCO Heritage site, L’Anse aux Meadows, which marks the place where Leif Erikson established a small Viking village over 1000 years ago. We needed our toques the morning we visited, but the chill north winds and gloomy sky only heightened the experience. The replica sod houses truly kept out the chill and the Parks Canada staff and volunteers, gave us a hands-on experience of what Viking life might have been like in the small settlement.

Then we wandered the soft green mounds of the actual archeological site and wondered how anyone might have found the remains of the village under this wind swept meadow. It is no wonder that the settlement remained buried for a thousand years.

Then in 1960, George Decker, a citizen of the small fishing hamlet of L’Anse aux Meadows, led explorer Helge Ingstad to what the locals called the “old Indian camp”. Then, under the direction of archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad (Helge’s wife), they carried out seven archaeological excavations there from 1961 to 1968. The Ingstads had studied the Icelandic sagas and had a hunch that this might be a Viking site. The Norse origin was confirmed based on similarities between artifacts found at the site and artifacts at sites in Greenland and Iceland.

We learned the story of the site’s origin by listening to translations of two Icelandic sagas in the book Voyages to Vinland. The sagas describe the voyage of Bjarni Herjólfsson who sighted land to the west of Greenland when blown off course en route from Iceland to Greenland in 985. Though he returned to Greenland without making landfall, around the year 1000 Leif Erikson approached Bjarni, purchased his ship, and mounted an expedition. Lief found a rocky and desolate place he named Helluland (land of flat stones; probably Baffin Island), then a forested place he named Markland (land of forests; possibly Labrador) and finally a verdant place with a mild climate he named Vinland (land of meadows or wine – depending on the pronunciation). There he built a small settlement that lasted 20 years.

Of course, when the Norse arrived they did not find a land devoid of people. As we learned at Port au Choix, native cultures had been on the Northern Peninsula for thousands of years. On the trail at L’Anse aux Meadows there is a sculpture called “The meeting of two worlds”. Created by Luben Boykov and Richard Brixel.

It symbolizes the meeting of human migrations: One that spread west from Africa through Asia and entered North America by land across the Bering straight (the First Peoples); and another that spread east from Africa through Europe and to North America by sea. The two groups met – and human migration circumvented the globe – when the Norse met the First Peoples at L’Anse aux Meadows.

That evening we went to St Anthony to hike Whale Watchers Trail.

The stunning trail took us on a series of boardwalks and short stairways across cliff top meadows in full flower and to an amazing lookout over the Atlantic Ocean and the cliffs of Fishing Point.

Equalling views of the landscape were views of whales. We must have seen 10 humpbacks in the hour and a half we were there. We saw them blowing, we saw their fins, we even a nice close “whale tail” (as my nearly 7 year old says). To my delight there were also Northern Gannets and Black Guillemots.

The next morning we went out in a Zodiac with Linkum Tours to share the water with the whales.

We saw Atlantic White-sided Dolphins jumping quite near to the boat, and then hidden away in a cove, a mother humpback whale and her calf. We saw them both surface, blown and dive (more whale tails). Best of all, we heard them! The cliffs acted like an amplifier transmitting the whale voices into the air. Watching and hearing them was magic.

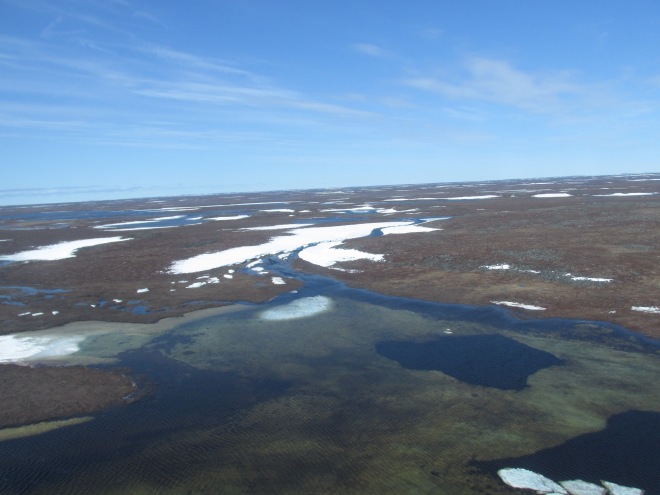

With whale voices still in our heads, we drove back down the Northern Peninsula past the low, gnarled tuckamore forests interspersed with fishing villages that dotted the coast like pearls. The air was clear and we could also see across the straight of Belle Isle into Quebec and Labrador. Our walking stop was a trail in Gros Morne National Park that took us across a huge peat bog to the base of the inland freshwater fiord of Western Brook Pond.

Western Brook Pond sits within the Lone Range Mountains in the northern part of the park. The fiord was carved when glaciers removed soft sediment from between the harder rock during the most recent ice age (from about 25,000 to 10,000 years ago). It became an inland “pond” (in Newfoundland inland fiords are called ponds) when it was cut off from the sea as land that had been pushed down by the weight of the ice sheets rebounded.

After a night in the Southeast hills of Gros Morne at Middlebrook Cottages & Chalets we were ready to explore the south side of Gros Morne National Park. We visited the Discovery Center on the South Arm of Bonne Bay and learned about the geology that makes Gros Morne famous. Then we hiked the Tablelands, a plateau of barren yellow rock, to experience it for ourselves.

From the trail it was amazing to look at the valley between the Tablelands and the Lookout Hills. On one side, the cliffs were barren yellow rock, but astonishingly just across the valley, there were trees on the slopes. Little grows on the Tablelands because the rock is not earth’s crust. Rather, it is a chuck of mantle that was dragged up half a billion years ago when Laurasia (Ancient North America) and Gondwana (Ancient Africa) collided. This chunk of mantle left on the surface, is part of what makes Gros Morne a UNESCO heritage site. This, and other wonders of geology in the 1,805 square kilometre park, provided the scientific evidence needed to support the theory of Continental Drift.

The Tablelands are barren because mantle is usually buried deep in the earth and is very unstable on the surface. This mantle rock is called peridotite and it is full of heavy metals and other chemicals that are toxic to plant life. It is yellowy orange because the iron in it is literally rusting when exposed to oxygen on the earth’s surface. Nevertheless, we saw several hardy plants that managed to grow (albeit sparsely) on the Tablelands. Most do this by being carnivorous, since the rocks of the barrens provide no sustenance. One such plant is the Pitcher Plant, which is the provincial flower. Another is the Common Butterwort, which has basal rosette leaves where glandular hairs secrete a sticky glue to catch insects. After much plant and rock watching, we completed the trail and were rewarded with the stunning and glacially carved Winter House Brook Canyon.

We spent the evening in Trout River, the tiny hamlet where a blue whale, whose skeleton ended up at the Royal Ontario Museum, washed up in April 2014. We walked the boardwalk overlooking the beach where the whale was found and took photos of the colourful houses overlooking the water.

At the wharf we saw fishing boats and fishers cleaning their catch. Then we dined at the Seaside Restaurant where we had cod and capelin fresh from the sea. Out the windows, we could see fishing boats returning to Trout River as the sun set over the cliffs. Back at the cottage, we built a fire and toasted marshmallows with the Milky Way arching across the night sky above us.

It was hard to leave the next day with the Tablelands ablaze in the morning light, but receding in the rear-view mirror. We covered the 600 km crossing of the Newfoundland from west to east much faster than the same distance going “up north” of Toronto. The Trans Canada highway was in good condition and there were frequent passing lanes to help smaller cars pass trucks as they slowed on the long inclines. As we learned in Gros Morne, the rock we crossed depicts the earth’s continental history – the collision of Laurasia and Gondwana that created the Appalachian Mountains (stretching Georgia to Newfoundland). The creation of the Atlantic Ocean after the continental plates split and water filled the space between them and the fascinating fact that the Africa plate left a small piece of itself behind. That piece now forms the eastern side of the Appalachians, including Bonavista and the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland. We left the rock of Laurasia behind and entered the rock of Ancient Gondwana.

Our rest stop was Terra Nova National Park where we hiked the Coastal Trail to Pissamere Falls.

The shore of Newman Sound looked like a lake in Ontario rather than the coast because the sea comes so far inland. But evidence that we were on the coast came when the trail met the beach and we found jellyfish, crab carapaces, and bladder wrack marking tide lines.

That night, our lodgings in Bertrem’s Beach House, a two-story cottage painted vibrant red, enchanted us all. We loved the cozy low ceilings and the kids took to hiding in the little upstairs nook beside the staircase where the ocean view was wonderful.

The next day, we had the puffins we’d come east to see – first at the Cape Bonavista Lighthouse and later (and even closer) at Elliston. Newfoundland & Labrador is home to hundreds of Atlantic Puffin colonies and the puffin is the provincial bird. The birds visit Newfoundland and other sea cliff islands around the North Atlantic to breed. They spend the winters out at sea.

We watched as these delightful birds entered and exited their cliff-top burrows and brought fish for their young (they eat capelin, herring, hake and other small fish). At times they all flew up and spiralled over the colony, possibly a protective behaviour.

Although few terrestrial predators can reach their island burrows, gulls are a problem and at Elliston we witnessed a gull eating an adult Puffin. This is natural, and escaping predation is part of the reason puffins mainly live at sea. It is also why their young fledge at night. But it was still heartbreaking, especially knowing that puffins mate for life and raise only one young per year over a six-week period.

At Elliston we also stopped at Sandy Cove Beach where we joined a flock of Sanderlings wetting our feet in the cold North Atlantic waters then scurrying away from the waves. Elliston is known as the root cellar capital of the world and we explored several root cellars (one of which contained an art installation). In the days before electricity, these dug out structures kept vegetables and other foods cool in the summer and not frozen in the winter. More than 133 root cellars have been documented in Elliston and some of them have survived two centuries.

Interspersed with puffin watching, we also hiked a small bit of the Cape Shore Trail to see the statue of John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto). In May 1497, the Italian explorer left Bristol, England on orders from King Henry VII to find an eastern passage to Asia. He found North America instead. No one knows for certain where he fist landed on 24 June 1497, but local tradition places his first steps in the New World at Cape Bonavista.

The sea caves at Dungeon Provincial Park were also a treat and we learned that such caves are formed when the sea pounds at cliffs and washes away the softer sedimentary rock. The hard rock then fractures and the waves pour into the spaces turning crevices into caves. Eventually the waves form a tunnel all the way around and when the roof collapses you get a hole – like the “dungeon”. Eventually the sea will carve out a sea stack where only a pillar of stubborn igneous rock remains.

We saw many sea stacks on the Skerwick Trail the next day. This 5.3 km loop skirts the north and south coasts of Skerwink Head, a rocky peninsula between Trinity and Port Rexton. The founder of this trail says it has the most scenery per linear foot than any other trail in Newfoundland and I believe it. We picnicked at a wooden lookout overlooking cliffs and sea. It was one of many spectacular picnic spots this trip. From our picnic spot we even spotted a whale far out at sea.

We also visited the Ryan Premises, another excellent Parks Canada Heritage site housed in a cluster of 19th century clapboard buildings over looking the Bonavista harbour. There we learned about Newfoundland’s fishing history and in particular the cod. Codfish have been part of Newfoundland’s culture and history for hundreds of years. First Peoples fished them and John Cabot commented on codfish abundance when he arrived in 1497.

For centuries the Europeans joined the codfish game and salted Newfoundland cod was fished, processed, and then shipped internationally. The fresh-frozen fish industry took over from salt cod after World War I and industrialized overfishing grew after World War II. By 1992 fish stocks had crashed and there was a moratorium on cod fishing. Newfoundlanders now needed to find a new way to make a living. A few ended up as interpreters at the Ryan Premises, sharing their personal connection to the fishing industry.

After days of good weather, we got soaked along the Trans Canada Highway from the Bonavista Peninsula to St. Johns. Gusty winds made our little rental car shudder and rain came down in sheets. We’d driven right into the outer edges of tropical cyclone ten. The weather stayed miserable in St John’s into the evening and thwarted our plans for dinner and a walk around the harbor. Instead we stayed close to our hotel and went for dinner at Mary Brown’s (a fried chicken chain that originated in Newfoundland and is now the fastest growing franchise in Canada). Because Newfoundlanders are so friendly, we ended up in conversation with one of the workers and she told us that we were eating in the location that trains people for franchises all over Canada. Small world.

The next day it was still windy and wet – the perfect weather for indoor exhibits at the Johnson Geo Center on Signal Hill. In fact, most of the exhibits are not just indoors, but underground. An entire wall of the Geo Center is rock exposed during the excavation for the building.

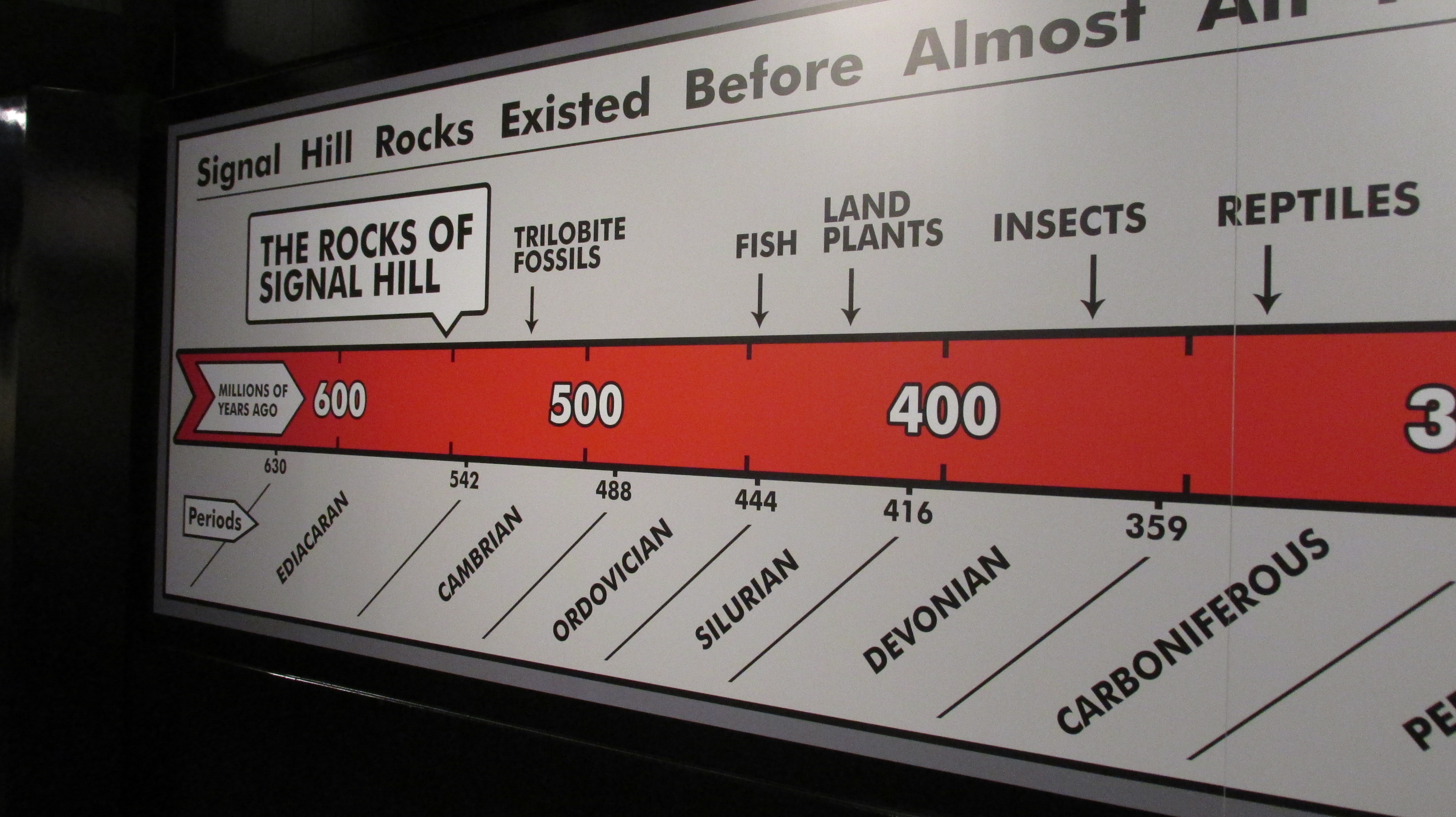

Of the many things we learned is that the rocks of Newfoundland and Labrador are incredibly old. Some of the rocks in the Torngat Mountains (Labrador) are 3.6 to 3.9 billion years old. Newfoundland’s rocks are newer, but still over half a billion years old, which is 450 million years older than the rocks of the Rocky Mountains. This is why we don’t find dinosaur fossils in Newfoundland. Dinosaurs may have walked on the rocks, but couldn’t have been fossilized in them because the rocks were already made when dinosaurs roamed.

Instead, in places like the UNESCO Heritage site at Mistaken Point, Precambrian fossils have been found (e.g., even older than the fossils of the Burgess Shale). These imprints of ancient soft bodies creatures were preserved because a volcanic eruption poured ash into the sea. The ash landed on the animals and eventually fossilized them (in much the same way that the people of Pompeii were preserved).

By the time we left the Geo Center the rain had stopped and the weather was clearing. We went to Signal Hill and hiked to the iconic Cabot Tower, built between 1897 and 1900 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of John Cabot’s landfall. The tower was also the place where Guglielmo Marconi received the world’s first transatlantic wireless signal in 1901. The Morse code signal for “S” travelled from Cornwall, England to the Cabot Tower.

The views of St John’s, its harbor and the rugged coast were spectacular.

We could see the Fort Amherst Lighthouse across the Narrows and in the distance the two lighthouses at Cape Spear where we headed there next.

The historic lighthouse at Cape Spear is nearly 200 years old and the oldest surviving in Newfoundland and Labrador. The other is a more modern working version. We hiked up to both and got breathtaking views of pink cliffs, blue seas and waves crashing as far as the eye could see in either direction.

Then we hiked to the most easterly point in Canada. Standing with our backs to the sea we knew that all of North America stretched out in front of us and there was nothing behind us until Ireland.

We finished the day with a walk downtown (taking advantage of the free street parking after 6 pm) and an amazing meal at the Bagel Café on Duckworth St.

We spent our last half-day in Newfoundland wandering. First along Harbor Drive watching big container ships get packed and ready to go. Then back alternating between Water St. and Duckworth St., taking in the “Jelly Bean Rows” of colourfully painted townhouses and also exploring the old business district and the pub district along George St.

Then we headed to the historic fishing village of Quidi Vidi. Where we watched artists work at the Quidi Vidi Plantation, a craft enterprise incubator (like a business incubator for emerging artists). From there we crossed a small footbridge and headed up a gravel path to the entrance of the East Coast Trail. There we joined locals out enjoying the Labour Day weekend picking blue berries and walking their dogs.

On the plane home – heading back to reality – I reviewed my pictures and marveled that we’d had only about 24 hours of bad weather in a 10-day trip. Newfoundland showed us her beauty in late summer glory – full of sunshine and free of bugs. We were fortunate. Still, my pictures hold evidence that Newfoundland is not a place of benign weather: from the tuckamore forest bent away from driving wind and crashing seas, to the gravel of the barrens, literally shattered by freeze thaw cycles and “death by a thousand cuts” weathering. Newfoundland’s beauty comes from this weather and its majesty was born from mountains bulldozed up in violet collision and scoured clean by glaciers.

It was an incredible trip.

I can’t wait to go back. Perhaps we’ll try a different season and next time and I’ll stand on a cliff top by those bent tuckamore trees and howl right into that salty wind above a pounding surf. I’ll howl “Thank you” for Newfoundland’s raw, majestic beauty.